Originally published Saturday Jan 31 2015; now updated with Sunday Feb 01’s developments!

My Twitter timeline has been full of Belgium.

I’m in San Francisco, but many of my developer friends are in Brussels for FOSDEM, an annual free software conference with 5000+ attendees, which this year had a Ruby “room” (like a track). Everyone seemed to be having a great time. I saw snapshots of chocolate waffles, beer, and most compelling of all, some distinguished gentlemen wearing lab coats for a joint talk. It looked really fun! I felt the familiar tug of wishing I were there.

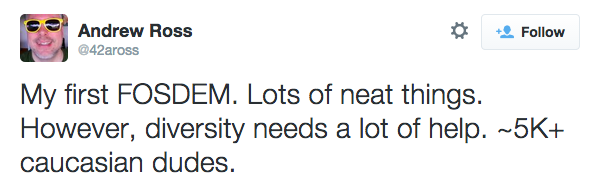

Then I saw this:

And then this:

Well…that kind of sucks. Feels a bit like the Ruby community of 2007. Ruby has come a long way, but I suppose not everyone has. But I can deal with this kind of thing. I’ve been changing people’s minds about what programmers look like for years.

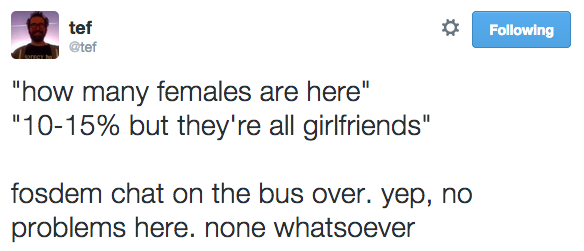

Then there was this:

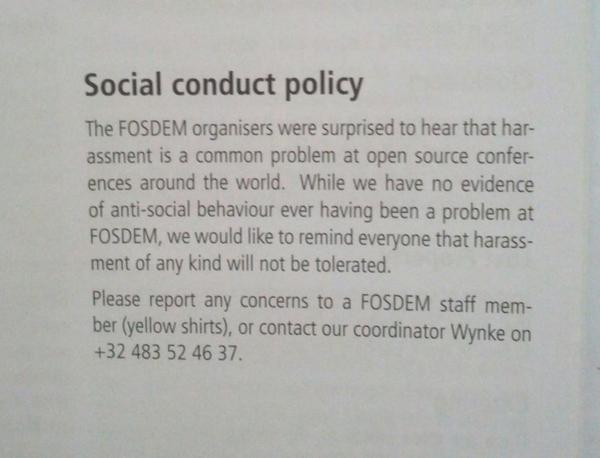

That’s when I knew FOSDEM wasn’t a place for me. The above is what serves as their code of conduct and anti-harassment policy. This wording first appeared at FOSDEM last year (see the third page), and was re-used verbatim this year. Individual rooms, like the Ruby room, were free to have a separate code of conduct if they wanted, but this was the only policy that covered the conference as a whole, or any of its social events.

I was somewhat taken aback. A conference that large with no proper code of conduct? I poked around the FOSDEM site and found nothing further – not even a reference to being “surprised” for the second year in a row. (Apparently it was only in the printed paper program.) Then I turned to Twitter, and I started to understand. Many people discussing this said some version of:

“Isn’t a code of conduct just meaningless paperwork?”

It seems that a real code of conduct is perceived by some folks as a politically-correct exercise that serves no real purpose. Perhaps the FOSDEM organizers felt that way. Honestly, I can see why. I want to explain why I still believe so strongly that all conferences need one.

I’ve been a developer since college, which at this point was a looooong time ago. In my early 20s – well before my speaking days – I went to conferences as an anonymous attendee. At these conferences, I regularly received unwanted and very persistent attention from other attendees. Sometimes from speakers. Sometimes from organizers.

Most of the time it was merely annoying. A few times it was profoundly alienating. But twice, it was absolutely terrifying.

That was harassment – all of it, even at the annoying level. I never reported any of it. Stories I heard from women who had reported similar incidents dissuaded me. When they were told about sexual imagery in slides and aggressive come-ons and being cornered at parties and offensive t-shirts and anonymous ass grabs and that guy who wouldn’t stop following me around, conference organizers just said, “If you’re uncomfortable, you can leave.” Often in combination with, “He says he didn’t, so I can’t do anything.”

20 Years Later…

I don’t get harassed any more. These days, the worst I have to contend with are the assumptions that I’m not technical, or that I’m somebody’s +1. That’s relatively harmless, compared to what I got previously. I’m not sure what caused the shift, but I have a few ideas:

- I married and had kids relatively young, so that may have removed me from the harassment demographic.

- Once I started speaking and organizing conferences, maybe I looked less like an easy mark.

- Perhaps – and this is the one I’d most love to believe – we’ve actually made some progress since the mid-90s. Maybe today, technical conferences are safer for women.

If this last one were true, those folks I talked about above would be right – a code of conduct would be meaningless paperwork, like the terms of service we all pretend to read when we install software.

But when I talk to young women in this field about conferences, they repeat my stories from the 90s back at me. While I have apparently aged out of harassment, women who are in that place right now contend with the same fear, the same dread, and the same fucked-up expectations that I did.

The difference is that now we have tools.

What You Can Do

I want to live in a world where it’s safe to attend a conference while female – no matter your age, appearance, or community status. That’s not the world we live in now.

The first step seems easy: just acknowledge that this is a problem. Tell the women interested in your conference that you’re aware of the issues, and you’re prepared to take them seriously if something happens. And that’s where a code of conduct comes in. That is, in fact, the whole purpose of a code of conduct. Properly written, it says, “Hey, we know this happens. Here’s what you do when it does.”

And that’s exactly where FOSDEM’s “social conduct policy” fell down.

It starts off with, “We’re surprised to hear this ever happens! In fact, it probably doesn’t.” Then it wraps up with, “But here’s what to do if it does.” That last bit is – sincerely – great. It’s exactly what you want to end with.

But imagine you’ve been harassed previously, and your memory of the experience provokes shame, stigma, and fear. Then you read the first part of this policy, which explicitly disbelieves your lived experience. How likely are you to report an incident, even if one should happen?

William Pietri summed up perfectly how this sounds to harassment survivors: “As people clueless about a problem, we remind you that if you report it to us, we probably won’t believe you.”

The authors of this policy meant well, but they alienated exactly the people they meant to reassure.

Alternatives

A proper code of conduct contains two critical parts: the “yes this happens” part, and the “here’s what you do” part. It must have both to be effective; otherwise, it does more harm than good. The FOSDEM folks did get some private negative feedback last year on their policy, which sadly provoked no change. After this post was published, however, and in response to attendee questions, FOSDEM stated publicly that they now know they need a code of conduct. I sincerely hope this bodes better than last year for change.

Here’s a great example they can start from. Many conferences I’ve been to over the last year have adopted anti-harassment policies based on this.

No Silver Bullet

Harassment is a complicated problem. Codes of conduct are not sufficient to solve it, but they are a necessary first step. We cannot fix a problem we do not acknowledge.

I will no longer consider attending or speaking at an event that does not implement a proper code of conduct. This has been my informal policy for some time, but it seems important now to say it out loud. I don’t imagine my personal declaration is weighty enough to sway conferences towards adopting a real code of conduct, but since I do quite a few conference talks (including this week at RubyConfAU), it will at least contribute to the rising tide.

So, FOSDEM: you can do better. Next year I hope to see a clear anti-harassment policy so I can attend what otherwise looks like an incredible event. And eat one of them OMG CHOCOLATE WAFFLES.

O M G G G G

Hi Sarah,

> That last bit is – sincerely – great. It’s exactly what you want to end with.

The problem with this part is that it doesn’t work right. I’m currently trying to report and while everyone is concerned, kind and no one argues, communication is rough and it shows that the staff is not prepared for this. The lack of policy means lack of guidance. It’s very aggravating. I’m trying to report staff misconduct.

I’m afraid this year’s social conduct policy is exacly the same.

left blank – Yeah, once you have a policy, you have to have the training and capacity to act on it. FOSDEM clearly has a lot of work to do in that department as well. I wish you luck.

Matijs – thank you, I have updated the post to reflect that.

Three things:

1. So unless you would have read those Twitter messages you wouldn’t have noticed anything wrong?

2. You’re saying “yes this happens”, what if as organizer you are truly and honestly unaware of any incidents? I have a hard timing admitting something I have not been reported or witnessed.

3. What do you consider harrasment – which you have experienced? Can you give examples?

Piotr, you clearly did not read the piece. So I’ll just ask you some questions of my own.

1. If conference harassment doesn’t happen, why would so many women lie about their experiences with it?

2. Is it possible for a woman at a mostly-male social gathering to have experiences that a man at the same gathering would not have?

3. Is it possible that women don’t report incidents of harassment precisely because of organizers with attitudes like yours?